You need to keep in mind that learning is more important than teaching. To foster learning, you should be aware of the most useful techniques a successful teacher usually does in class. On the other hand, you also need to know what prevents learning. Here are my top 13 tips for conducting an efficient and effective English lesson. Check which ones you already do and which ones you ought to focus on more in the future.

1 . Build an instant rapport with learners. From the first lesson, try to establish a friendly rapport with your students. Use their names and involve them equally in activities. Bring energy into the class with your friendly and nice manner from the start.

2 . Grade your language. Speak clearly and naturally to give the students a good input of the target language. Avoid using metalanguage, especially in low-level classes.

3. Reduce your teacher talking time (TTT). Aim for more students’ talking time (STT). Let your students practice their English, not you. Make your class more student-centered

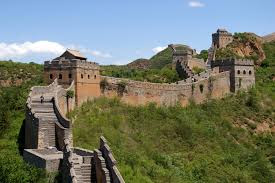

4. Enhance your lessons with visuals. Use a variety of visual materials such as pictures, videos, and PowerPoint slides that achieve your lesson aims and make your lesson more dynamic. A picture is worth a thousand words.

5. Give clear, simple instructions. Break the instructions down and use instruction checking questions (ICQs) to check if the students have understood. Don’t ask general questions like “Do you understand?” If you’re using worksheets, it’s better to chest the worksheet, point to the exercise and give instructions before distributing the worksheets. Otherwise, the students will start reading and won’t pay full attention to your instructions.

6. Vary the interaction patterns. Don’t opt for teacher-students (T-Ss) interaction only. Learning English happens faster when students interact more with others. Pair work and group work would maximize the students’ talking time and encourage peer-teaching. Make sure your lesson plan includes individual, pair, and group work.

7. Don’t echo the students’ answers. Don’t get into the habit of repeating your students’ words (I’m afraid I do it sometimes). When you do that, you’re sending the message to your students that you’re the authority in class and there is no need to listen to each other. Don’t echo; ask the student speaking to raise their voice if the others can’t hear him/her.

8. Avoid Over-helping. When the students are doing a task or giving answers in pair or whole class feedback, don’t worry that they can’t make it. Don’t complete their sentences; rather, give them a sufficient time to think, reflect, and produce their answers. Use gestures, one-word prompt and if those don’t work, ask another student for help to encourage peer-support/teaching. Be the last one to speak, not the first one. Help them be autonomous learners.

9. Circulate and monitor. While the students are working on a task, whether individually or in pairs, you should circulate and monitor them to make sure everyone is on task. You might need to help those who still do not understand, or warn those chatting with their classmates, but don’t interfere or over-help.

10. Vary the feedback stages. Instead of constantly nominating individual students to provide answers to the whole class in a T-Ss interaction, you can display the answers for them on the white board/screen to check. You could ask some students to come to the board and write the answers for the class after a brainstorming activity. Alternatively, you can provide one student with half of the answers and his/her partner with the other half. They work in pairs to exchange the answers; that would make the feedback more student-centered.

11. Let your Students practice grammar. Don’t worry if the students don’t get the concept of the target language 100% from the first time, they still need a lot of practice to grasp the meaning and to be able to use the TL productively. Avoid long explanations; provide adequate controlled, semi-controlled, and freer-practice activities to help the students encounter and make more decisions about the TL over a number of contexts.

12. Set a time limit. Allocate a time limit for each task to get the students more challenged and focused. Stop the activity if most of the students have finished before the time is over or give more time if most of them are still involved.

13. Encourage your Students to speak English more. Don’t hear or understand your students when they talk to you in their mother tongue, accept only English.

Would you add any other useful techniques to the above list? Let us hear from you?

Would you add any other useful techniques to the above list? Let us hear from you?